Introduction

In the run up to COP26 in November 2021, politicians, policy-makers, corporations and researchers have become more and more vocal in embracing ‘nature-based solutions’ as a way of tackling the urgent challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. The 2021 Dasgupta Review, the framework for the UK government’s approach to reversing biodiversity loss, argued for increasing investment in nature-based solutions; and they have been a major theme of COP26 with the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee urging the COP26 President to ensure that nature-based solutions would be included in the COP26 negotiations, the final decision text, and the Nationally Determined Contributions of the Parties. Governments around the world have taken up the concept through a multitude of forestry and other programmes, including the UK government’s £3 billion commitment to climate change solutions that protect and restore nature and biodiversity over five years; and private sector giants such as Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Shell and Unilever who have invested billions since 2019 in the restoration and protection of nature’s assets.

But what exactly are nature-based solutions? And is all the excitement justified? More recently, there have been a number of voices critical of the broad enthusiasm for nature-based solutions – NbS – as the key to reversing climate change and biodiversity loss. In this article, we set out the opportunities that NbS bring, alongside their limitations; and provide some examples of how Triple Line has been working with NbS over the years.

What are nature-based solutions?

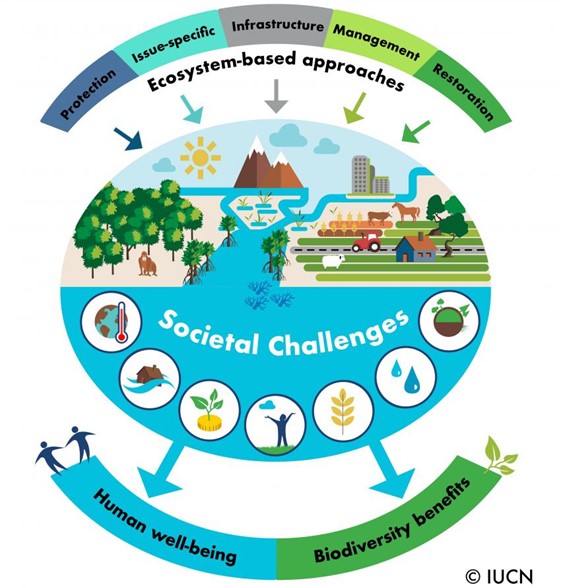

The concept of nature-based solutions first emerged towards the end of the 2000s when the World Bank and IUCN drew attention to the importance of biodiversity for climate change mitigation and adaptation. It was at COP21 in Paris in 2015 that IUCN put forward NbS as a way of both adapting to and mitigating climate change, while at the same time securing water, food and energy supplies, reducing poverty and driving economic growth. Since then, the concept has gained traction in international policy and business agendas as hard-engineered interventions such as sea walls and embankments have failed to protect people and their habitats from the consequences of climate change. NbS are defined by IUCN as:

actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural and modified ecosystems in ways that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, to provide both human well-being and biodiversity benefits.

Interpretations of NbS vary widely, with much of the recent attention having been on tree planting for carbon sequestration. The concept has expanded from an initial focus on ecosystem-based adaptation to encompass urban green infrastructure, climate change mitigation, sustainable agriculture and many other concepts – such as ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction, natural infrastructure, blue infrastructure and forest and landscape restoration.

The opportunities of NbS

Protecting and restoring nature is key to tackling climate change. When nature is restored and protected, biodiversity returns and our climate becomes healthier, thereby contributing to human wellbeing. This is one of the greatest opportunities of NbS: the potential to tackle the challenge of climate change – at relatively low cost – while delivering multiple additional benefits for people and nature. Below we consider some examples of these opportunities in terms of climate change adaptation and climate change mitigation.

NbS and climate change adaptation

Adaptation to actual or expected climate change effects involves changing social, economic or ecological processes, practices and structures to reduce people’s vulnerability and increase their resilience to the impacts of climate change. They can take many forms, including NbS such as:

- Supporting agroecology practices – sustainable farming that seeks to balance relationships between plants, animals, people, and their environment. By taking a systems approach, biodiversity on farms is increased, and diversity of seeds and crops provides options for adaptation. Socially equitable food systems are established through community-based and collective action; and reliance on community seed systems supports people’s resilience to extreme events.

- Agroforestry and climate-smart agricultural techniques that help to diversify crops and enhance productivity of existing agricultural land, improving the nutrition and resilience of vulnerable populations without the need to expand farmland.

- Support for livelihood diversification can provide incentives for economic activities to move away from key drivers of deforestation – for instance through training to increase productivity and/or profitability, or switching from timber to non-timber forest products – thereby reducing the rate of forest or wetland clearance.

NbS and climate change mitigation

The 2019 IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land emphasises the potential of NbS for climate change mitigation, including avoided deforestation and land degradation, as well as carbon sequestration. Examples include:

- Ecosystem restoration, conservation and management (of tropical forests, dry forests, mangrove forests, watersheds) such as tree planting, community-based forest management practices to restore or conserve ecosystem services.

- Curbing deforestation, especially in tropical and subtropical regions, by promoting sustainable land use, reducing deforestation pressure, and applying a landscape management approach.

- Integrated water resource management (IWRM) approaches that combine NbS (e.g. planting trees, reforestation, or agroforestry with indigenous species) with ‘gray infrastructure’ interventions to restore water supplies for local communities.

Limitations and challenges of NbS

Despite its popularity as an approach that offers huge potential to address both the causes and the consequences of climate change while supporting biodiversity and enhancing human wellbeing, NbS have a number of limitations and challenges:

NbS can be a distraction from the need to decarbonise energy systems. NbS can distract from the need to rapidly phase out fossil fuel use, with an over-emphasis on planting trees rather than investing in a range of ecosystems. The extent to which NbS can contribute to offsetting continued fossil fuel emissions has been questioned by a number of researchers for the following reasons.

- Constraints on land area and tree growth dynamics limit the amount of carbon that can ultimately be removed by tree planting or forest regrowth. Tree plantations can take decades until they are able to sequester carbon.

- There are risks of stored carbon being released at a later date due to deforestation and wildfires as global warming continues. According to the IPCC, without a rapid phase out of fossil fuel use, climate change threatens to turn emissions sinks into sources, as vegetation becomes stressed, wildfires become more frequent, and soils and oceans warm.

- There is a risk of damage to biodiversity, if enthusiasm for planting trees results in the creation of large monocultures.

- Over-reliance on NbS as a cheap offsetting option in government or corporate mitigation policies risks distracting from the urgent need for aggressive and rapid greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction in all sectors of the economy. The challenge is how to direct funding towards well-planned NbS projects that do not delay decarbonisation.

Some stakeholders feel that NbS have been co-opted by corporations to mislead investors and the public into believing that the company is more environmentally sound than it truly is – greenwashing. In an open letter to the COP26 Presidency, a group of leading environmental and human rights NGOs warned that its flagship NbS policy risks greenwashing some of the biggest polluters on earth. The signatories, from both high- and low-income countries, warn that the concept has been hijacked by the oil and gas industry and other heavy polluters to avoid reducing their emissions at source by nominally offsetting their emissions elsewhere. They warn that the claims made that NbS can account for up to a third of climate mitigation potential by 2030 are simplistic and based on implausible assumptions; and that, after 15 years, natural carbon offsets have proven largely ineffective in reducing emissions or protecting forests.

Limitations in funding. According to WWF, there is a huge funding gap in investments in nature: for preserving and restoring ecosystems alone, the required investment is estimated at US$300-400 billion per year, whereas only US$52 billion is being invested annually in such projects. Moreover, a disproportionate amount of funding seems to be being channelled towards tree planting, as a high-profile study has recently discussed.

Potential adverse impacts on indigenous peoples and local communities. Indigenous peoples have been increasingly recognised as the custodians of the environment, protecting their lands, forests and respecting wildlife, with a key role to play in tackling the biodiversity and climate crises. Nevertheless, they have tended to be excluded from decisions which involve ecosystem protection and management, and violations of indigenous rights continue with impunity. A study of 27 countries found mixed results in terms of reforming indigenous rights and tackling violations of existing rights, resulting in loss of livelihoods, displacement, marginalisation and psychological trauma. Large private timber concessions and plantations continue to seize indigenous lands, while new national parks, protected areas and forest reserves appropriate land with territorial and customary rights. Mining and forestry rights continue to be granted to corporations and elites in countries such as Guatemala, Gabon, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Republic of Congo and Indonesia without consulting communities or taking into account the impacts on their livelihoods and other needs. In areas of coca production, such as Colombia, military incursions and drug-eradication programmes provide cover for lawlessness and abuse; while in Brazil the creation of large plantations and new protected areas has been accompanied by coercion and physical violence, the destruction of homes, the confiscation of livestock and prohibition on the collection of forest products, agriculture and fishing. Some conservation programmes have alienated local communities by using them for labour while restricting their access to what were previously common-pool ecosystem resources. This forces communities to find alternative fishing or hunting areas and can lead to negative impacts on stocks and biodiversity.

Some mitigation measures can increase the threat to indigenous peoples’ territories and their coping strategies, as in the case of biofuel initiatives. According to UNEP, while biofuel initiatives are meant to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they may affect the ecosystems, water supply and landscape on which indigenous peoples depend, ultimately leading to an increase in monoculture crops and plantations and a consequent decline in biodiversity, food and water security. At least a quarter of the world’s land area is owned, managed, used or occupied by indigenous peoples and local communities. It is therefore crucial that they are included in decision-making and in designing and implementing solutions for ecosystems to ensure that actions and investments do not have detrimental effects on their lives and livelihoods as well as on biodiversity. Many conservation and development agencies which have been working with indigenous peoples fear that large-scale NbS could trigger huge demand for land, dispossessing communities, and exacerbating displacement and food insecurity.

It is worth mentioning ongoing initiatives that aim to address these issues. Recently, nine grant-makers pledged US$5 billion for conservation efforts to address the threats to biodiversity and help curb climate change – taking a new approach that will support a ’new generation’ of programmes led by local communities. Meanwhile, at the World Leaders Summit at COP26, governments and private donors announced a US$1.7 billion pledge to help indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) protect the biodiverse tropical forests that are vital to protecting the planet from climate change, biodiversity loss and pandemic risk. This is in recognition of IPLCs’ role as guardians of forests and nature, and guarantees them a role in decision-making and the design of climate programmes and finance instruments.

Triple Line’s work on NbS

Triple Line supports clients in addressing some of the greatest development challenges related to our changing environment and climate. We have applied NbS in various forms to explore different mechanisms for climate change mitigation and adaption, particularly in the areas of reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) and the EU’s Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) programme. We have also worked on incubation of small-scale, community-based, low-carbon enterprises and market linkages; social forestry and community-based natural resource management to reduce deforestation in forest rich countries. We support clients to identify low-carbon, resilient and green options for urban infrastructure and environments – ‘eco-industrial’ approaches – that manage power and water demand, using renewable energy and surface water sources.

Some of these have shown good results. Since 2013, we have worked with the FCDO’s Forest Governance, Markets and Climate (FGMC) programme, to tackle forest governance failures in developing timber-producing countries in order to reduce deforestation while helping vulnerable communities to improve their livelihoods. In Indonesia, we led the Evaluation Management Unit of the Forest, Land-Use and Governance (FLAG) programme working with the UK Climate Change Unit, the Government of Indonesia and local partners to reduce the rate of deforestation and peatland degradation in Indonesia and contribute to Indonesia’s GHG emissions reduction targets. In Myanmar, our Cities and Infrastructure for Growth (CIG) programme team identified a range of opportunities to enhance resilience to climate hazards in four cities (Bago, Pathein, Taunggyi, and the capital, Naypyidaw) by applying NbS including climate-smart water management strategies (eco-drainage, smart water monitoring, natural wastewater treatment), the use of biogas for energy efficiency, and composting of food and organic waste.

In Africa, we worked with FAO and national stakeholders in the DRC to develop its National Forest Monitoring System (NFMS), to provide information on activities related to changes in forest land use and help DRC meet its REDD+ commitments. In Ethiopia, we evaluated the FAO’s country programme focused on three government priority areas – crop production, livestock and fisheries, and sustainable natural resource management – taking a cross-sector approach focused on issues of resilience building, climate change and gender. In particular, the analysis of sustainable natural resource management assessed projects for land restoration in arid and semi-arid landscapes, watershed and rangeland management, forest monitoring systems, sustainable wood fuel management and tenure of land, fisheries and forests.

The way forward

With our experience of designing, monitoring and evaluating NbS interventions in the field, Triple Line recognises that NbS need to be understood in a holistic way, as one of many angles of approach that need to be balanced in order to tackle climate change and its impacts, and restore and protect ecosystems and their diversity.

Lack of clarity over what count as NbS needs to be addressed. Ambiguity facilitates greenwashing, whereby narrowly-conceived NbS are used to sanction business-as-usual activities and mask the urgent need for more systematic change.

The IUCN Global Standard for NbS emphasises the need for clear parameters and a common framework to guide NbS approaches, prevent unanticipated negative outcomes or misuse, and help funding agencies, policy makers and other stakeholders assess the effectiveness of interventions. It sets out eight criteria (with 28 indicators) to help designers and users of NbS apply, learn and continuously strengthen and improve the effectiveness, sustainability and adaptability of their NbS interventions. These eight criteria provide a strong foundation to guide future thinking about how NbS can be applied in a meaningful, honest and impactful way:

- NbS effectively address societal challenges

- Design of NbS is informed by scale

- NbS result in a net gain to biodiversity and ecosystem integrity

- NbS are economically viable

- NbS are based on inclusive, transparent and empowering governance processes

- NbS equitably balance trade-offs between achievement of their primary goal(s) and the continued provision of multiple benefits

- NbS are managed adaptively, based on evidence

- NbS are sustainable and mainstreamed within an appropriate jurisdictional context

In the run-up to COP26, 20 UK-based organisations developed a complementary set of guidelines as a call to businesses and governments to ensure investment in NbS is channelled to the best biodiversity-based and community-led NbS and does not distract from or delay urgent action to decarbonise the economy. These are:

- NbS are not a substitute for the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels and must not delay urgent action to decarbonize our economies.

- NbS involve the protection, restoration and/or management of a wide range of natural and semi‐natural ecosystems on land and in the sea; the sustainable management of aquatic systems and working lands; or the creation of novel ecosystems in and around cities or across the wider landscape.

- NbS are designed, implemented, managed and monitored by or in partnership with Indigenous peoples and local communities through a process that fully respects and champions local rights and knowledge, and generates local benefits.

- NbS support or enhance biodiversity, that is, the diversity of life from the level of the gene to the level of the ecosystem.

At Triple Line, we are excited about working with the public and private sectors to take forward these guidelines and principles and explore how NbS can be applied in a holistic way to help combat the twin challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. We applaud the focus on respecting the rights and livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local communities, and welcome the scope this brings to ensure that interventions explicitly take into account the needs of disadvantaged groups such as women, girls, youth and those affected by disability, who are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts.

Written by Shoa Asfaha and Binh Tran, Triple Line

References

MacKinnon K, Sobrevila C, Hickey V et al (2008) ‘Biodiversity, climate change and adaptation: nature-based solutions from the Word Bank portfolio’. World Bank, Washington, DC

IUCN (2009) ‘No time to lose: make full use of nature-based solutions in the post-2012 climate change regime’. Position paper on the fifteenth session of the conference of the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 15). IUCN, Gland

Chausson, A. et al., (2020) ‘Mapping the effectiveness of nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation’ Global Change Biology

Seddon, N et al (2021) ‘Getting the message right on nature- based solutions to climate change’, Global Change Biology

IPCC (2019). ‘Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems’

WWF. (2020). Bankable nature solutions. Worldwide Fund for Nature

Alcorn, J. & Molnar, A. (2018) ‘Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Rights and Steps Toward Reform in 27 Countries’

Fairhead, J., Leach, M., & Scoones, I. (2012). ‘Green Grabbing: A new appropriation of nature?’ Journal of Peasant Studies, 39, 237– 26; Srivastava, S., & Mehta, L. (2017). ‘The social life of mangroves: Resource complexes and contestations on the industrial coastline of Kutch, India’. ESRC STEPS Centre

Mora, C., & Sale, P. F. (2011). ‘Ongoing global biodiversity loss and the need to move beyond protected areas: A review of the technical and practical shortcomings of protected areas on land and sea’. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 434, 251– 266

David Kaimowitz (2021) ‘Indigenous Peoples Must be Central to Tackling the Climate Crisis’, IISD SDG Knowledge Hub

Ford Foundation (2021) ‘Governments and private funders announce historic US$1.7 billion pledge at COP26 in support of Indigenous Peoples and local communities’